African-Americans at Pebble Hill

Caroline Marshall Draughon Center for the Arts & Humanities

Download a PDF of our booklet on the history of Pebble Hill.

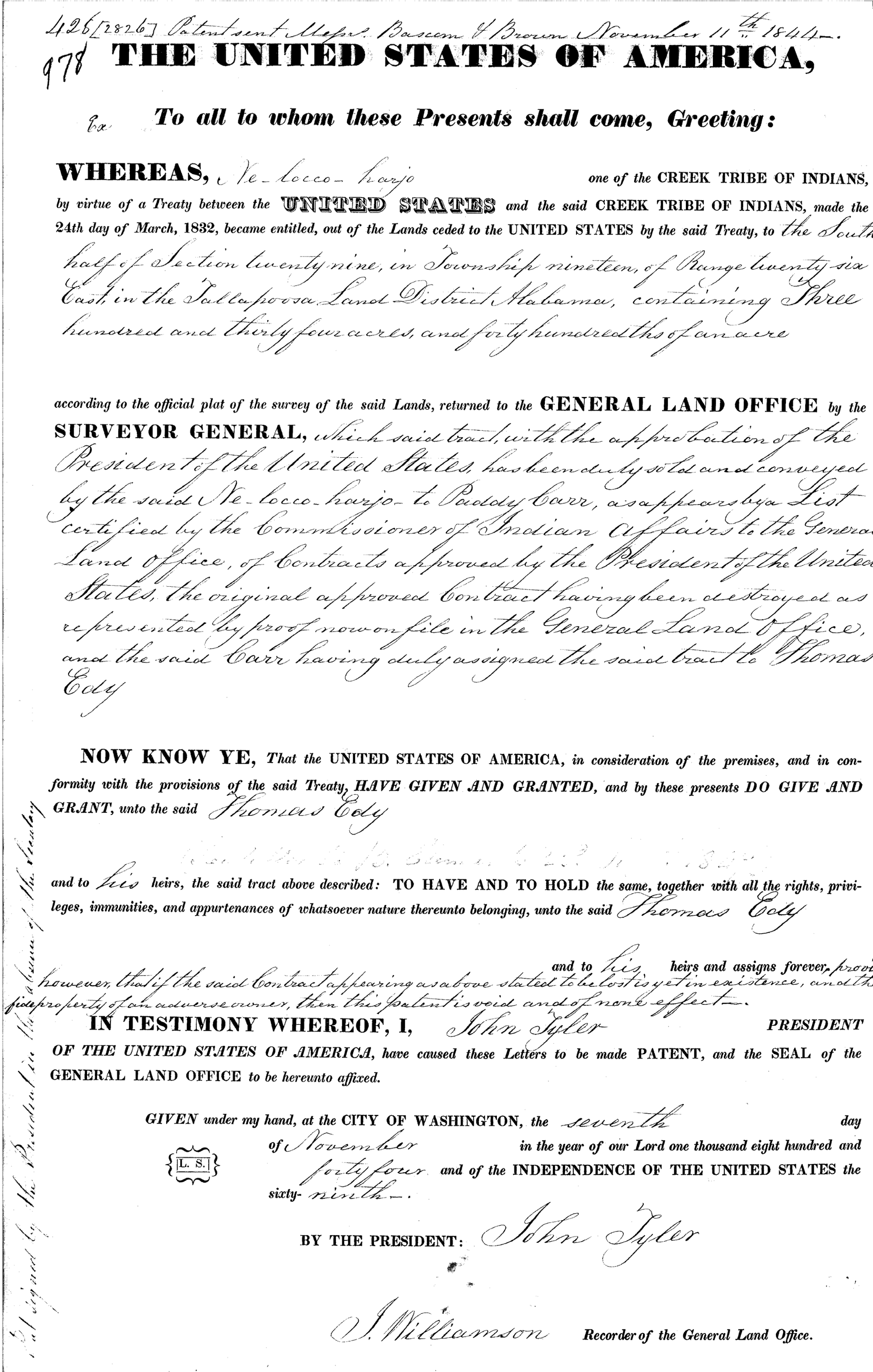

In 1832, the Creek Nation signed the Treaty of Washington (sometimes called the Treaty of Cusseta), whereby they officially extinguished tribal claim to their land. Under the terms of the treaty, individual Creek heads of household were awarded 320 acres (with 640 acres for chiefs). Individuals could sell this property or remain on it as long as they wished. The treaty ended Creek tribal government east of the Mississippi. The treaty was meant as a way for the Creek people to retain possession of their land, but violence and unprecedented fraud by land speculators who used a variety of techniques to obtain these land reserves left the majority of Creeks either homeless or unable to obtain control of their property. When violence broke out over the frauds and harrassment in 1836, the United States used the war as an excuse to suspend the treaty provisions and order the forced removal of the Creek people.

Many Creeks, such as Paddy Carr, acted as agents for speculators and land agents. Many of the deeds so frequently seen with the names of individual Creeks were likely obtained by fraud. There is no record of the exact manner that Carr obtained the allotment of Nelocco Harjo, which includes the land where Pebble Hill sits. Nelocco Harjo may have sold it willingly or, like so many other parcels, it may have been obtained by subterfuge or outright fraud.

Nathaniel J. and Mary K. Scott

Nathaniel J. and Mary K. Scott came to east Alabama in the 1830s, part of the wave of settlers who poured into the area after the United States acquired the territory from the Creek Indians. For Nathaniel Scott, the move to Alabama was part of a gradual movement westward. Born in northeast Georgia, he migrated to Harris County, Georgia in the late 1820s. In 1829, he married Mary King Embree of Columbus, Georgia. In the late 1830s, the Scotts, their young children, and their African-American slaves joined Nathaniel Scott’s brother and half-brother in moving to Macon County, Alabama. Nathaniel and Mary Scott quickly accumulated land and more slaves, becoming prosperous planters and slaveholders.

The Scotts helped build the town of Auburn, which was founded by Nathaniel Scott’s half brother, John J. Harper. They were early members of the Methodist Church in Auburn, and in 1839, Nathaniel Scott was appointed a town commissioner. In 1841, he became the first Auburn resident to represent Macon County in the Alabama House of Representatives; in 1844, he was elected to that office again. In 1845, he was elected to the state senate.

In 1846, the Scotts purchased approximately 100 acres of land just east of Auburn for $800, and likely constructed Pebble Hill there soon after buying the property. Situated close to town, Pebble Hill was the Scotts’ primary residence, though they continued to own farm land in the area surrounding Auburn. While living at Pebble Hill, they actively supported the development of schools in the growing town. In 1847, Nathaniel J. Scott helped organize the Auburn Female College, which was later renamed the Auburn Masonic Female College. In 1850, fourteen students who were attending schools in Auburn lived with the Scotts at Pebble Hill. In 1856, Nathaniel Scott and other Auburn Methodists established the East Alabama Male College, which many years later became Auburn University. He served as a member of the college’s Board of Trustees from 1856 until 1863.

Meanwhile, Scott continued his political career, serving as state senator in the 1847. During his first term in the state legislature, he became acquainted with Alabama politician and writer William Lowndes Yancey, a leader of the secession movement and an ardent defender of slavery. By 1860, Scott, like Yancey, supported seceding from the Union. After the Civil War began in 1861, two of Nathaniel and Mary Scott’s sons – Embree and John – joined the Confederate Army. In 1862, Embree Scott died of illness following the Battle of Seven Pines in Virginia. Nathaniel J. Scott died the following year, leaving Mary Scott and her grown children to manage the family’s plantations.

During the tumultuous years that immediately followed the defeat of the Confederacy in 1865 and the emancipation of slaves, Mary Scott sold Pebble Hill.

Mary Virginia Riley

After Mary Scott sold Pebble Hill, absentee landowners owned the property until 1876, when Mary Virginia Riley purchased it. The little information available about Riley raises tantalizing questions about her identity and how she supported herself and her family as a widow in late 19th-century Alabama. Born in Washington, D.C. in 1828, she married before she was twenty years old, but the name of her husband remains unknown. By 1860, when she was thirty-two years old, she was a widow living in Montgomery, Alabama with three young children. The 1860 census did not list an occupation for her, she owned no real estate, and her personal estate was valued at $200. By 1872, she had likely moved to Lee County, where her daughter Amelia married Frank A. Hodges, a cotton buyer and son of a wealthy Mobile merchant. In 1876, Mary Riley’s son, John Milton Riley, married Jennie Clower, the daughter of an Auburn farmer. Her children’s marriages into well-educated and well-to-do families suggests that Mary Riley herself was educated and came from the middle or upper class.

It is unclear to what extent Mary Riley used the property as farm land. In 1880, only seven of the farm’s 97 acres were under cultivation, and Riley produced only five bales of cotton. No records of the farm’s operation or products after 1880 have been located; she may have later rented the land to tenants or sharecroppers. Mary Riley lived at Pebble Hill until her death in 1907.

The Yarbrough Family

The Yarbrough family owned Pebble Hill from 1912, when Dr. Cecil S. and Bertha Mae Yarbrough purchased it from Mary Riley’s daughter, until 1982. Cecil Yarbrough was born in Orion, Alabama in 1878, and studied medicine at the University of Tennessee. Born in Auburn in 1881, Bertha Yarbrough was the daughter of Oscar Grout, a farmer who owned land on the outskirts of Auburn. She graduated from Alabama Polytechnic Institute (later Auburn University) in 1900, just eight years after the college first admitted women. They married in 1903, and settled in Auburn, where Dr. Yarbrough established a medical practice. Cecil and Bertha Yarbrough had five children, three of whom were born after the family moved to Pebble Hill in 1912. In 1927, Bertha Mae Yarbrough died at the age of 45. The following year, Dr. Yarbrough married Mary Strudwick Yarbrough of Demopolis, Alabama. Dr. Yarbrough died in Auburn in 1946, and Mary Yarbrough died in Mobile, Alabama in 1967. Clarke S. Yarbrough inherited Pebble Hill from his mother, and owned it until 1982.

Dr. Yarbrough served several terms as mayor of Auburn, and a term as representative to the Alabama House of Representatives. He first held the office of mayor from 1916 until 1918, when he joined the U.S. Navy as a medical officer following the United States’ entry into World War I. After returning to Auburn in 1919, he was soon re-elected mayor, and served in that post until 1928. In 1922, in cooperation with other local politicians and powerful alumni of Alabama Polytechnic Institute (API), Yarbrough successfully fought an effort to move the university from Auburn to Montgomery, the state capitol. He again served as mayor again from 1936 to 1944. During his terms as mayor, he led efforts to improve the town’s roads and infrastructure, and welcomed President Franklin Delano Roosevelt during his 1939 visit to Auburn.

In the seventy years that the Yarbrough family owned Pebble Hill (1912-1982), API grew from a small land grant college into Auburn University, one of the state’s leading research institutions. Like many Auburn residents during this period, the Yarbroughs’ lives were closely intertwined with the growing university. Most of the Yarbrough children attended API, and Dr. Yarbrough served as acting director of student health services at the university in the last year of his life. For much of the time that the Yarbrough family owned Pebble Hill, they rented at least part of the house – as well as some of the outbuildings – to students at the university.

The expansion of the university contributed to the transformation of the landscape surrounding Pebble Hill from farm land into part of the town of Auburn. When the Yarbroughs purchased the property in 1912, it encompassed 95 acres of farm land. Particularly after World War II, the areas east of Pebble Hill became more densely populated as the number of students and town residents grew. Between 1945 and 1980, the Pebble Hill property itself was subdivided. Student apartment complexes as well as single family homes were constructed along Magnolia Avenue, while much of the land to the east of the house was subdivided for residential and commercial development. The transformation of Pebble Hill and the surrounding land during this period reflects the growth of the town during the late 20th century.

African-Americans at Pebble Hill

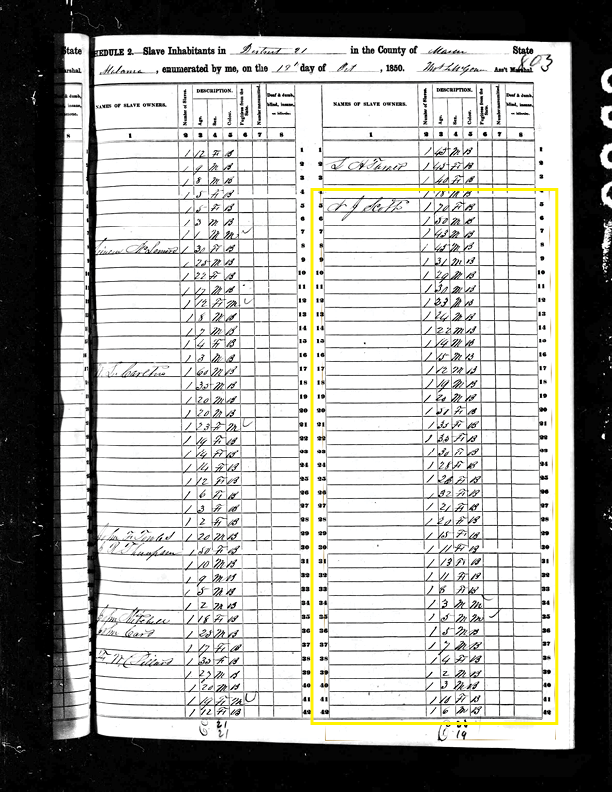

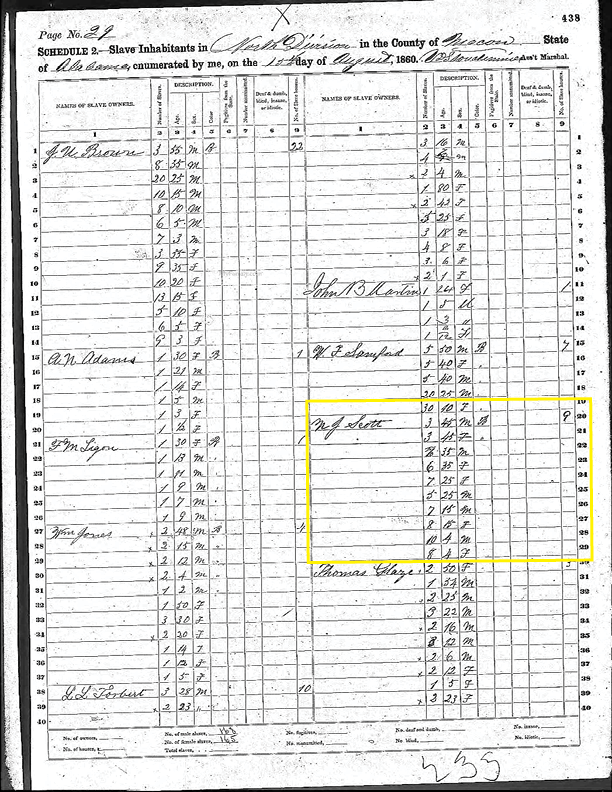

African Americans played central roles in the development of Pebble Hill. They built the house and outbuildings, cultivated the land, maintained the house and grounds, prepared food for members of the household, and cared for the children who grew up there. Enslaved African Americans were among Pebble Hill’s first residents. In 1850, three years after Nathaniel and Mary Scott purchased the property, he owned 38 enslaved persons ranging in age from two to 70. Ten years later, in 1860, he owned 63 enslaved persons. Not all of these people lived at Pebble Hill; many of them probably resided on the Scotts’ farm lands outside of Auburn.

Enslaved African-Americans at Pebble Hill likely performed domestic labor such as cooking, cleaning, laundry, and child care. Others may have cared for horses and other livestock, and cultivated vegetable gardens. Enslaved carpenters, masons, and blacksmiths performed maintenance and repair on the buildings, furniture, and equipment at Pebble Hill. Unfortunately, few written records remain to document the lives of Pebble Hill’s enslaved men, women, and children.

Learn about Major Harper and Betsy Scott

The end of the Civil War in April 1865 brought freedom for enslaved persons throughout Alabama. Soon after the war’s end, an African-American community developed in the area immediately to the south of Pebble Hill. It is possible that some of the former enslaved persons from Pebble Hill settled in this area.

African Americans who resided in the area worked at Pebble Hill from the late 19th century through the mid-20th centuries. Mary Riley hired African-American workers to assist with farming, and may have employed domestic workers as well. Prior to her death in 1907, Riley transferred a small strip of land at the south edge of the Pebble Hill property to James Bailey, an African American who was working as a mail messenger in 1900. Further research is needed to determine what the connection was between Riley and Bailey, and why she transferred land to him. Throughout much of the time that the Yarbroughs owned the property, they employed John and Naomi Neloms, both of whom were born in Alabama and lived in Auburn. The Neloms’ children spent time at Pebble Hill while their parents were working, and the family developed an attachment to the house. Further study of the personal and economic relationships between the white owners of Pebble Hill and local African-Americans in the late 19th and early 20th centuries promises to illuminate the history of race relations in Auburn.

Caroline Marshall Draughon Center for the Arts and Humanities

In 1974, Clarke and Mona Yarbrough sold the property to the Auburn Heritage Association. It was placed on the National Register of Historic Places on May 16, 1975. In 1985 the property was donated to Auburn University, and the Center for the Arts & Humanities was established. Commemorating the life and work of a beloved first lady of Auburn University, the Center was named in honor of Caroline Marshall Draughon in 2007. Born in Orrville, Dallas County, Alabama, in 1910, Draughon came to Auburn with her husband, Ralph Brown Draughon, in the fall of 1931 when he accepted a position in the Alabama Polytechnic Institute history department. From 1947, when Dr. Draughon was named acting president of the Alabama Polytechnic Institute, until his retirement in 1965 as president of Auburn University, "Miss Caroline" was a familiar and welcoming figure on campus.